I’m struggling to pinpoint exactly what it is I feel about No Man’s Sky. I find the game hypnotic and immersive, but also frustratingly jarring. I love its scope and scale, but am also frequently disappointed by its lack of variety. I love the way it lets you build your own story, but I also wish there was more of a structured narrative to pull me through it.

You see, it’s a game that is simultaneously all these things…a game that contradicts itself from start to last. It’s a game that’s not really a game until you have to manage your inventory or shoot laser beams at flowers to gain chemical elements, at which point it is the most game. It’s a game that I wish had the balls to not be a game at all, but also a game in which I wish had more game to it.

(Okay I’ll stop saying ‘game’ now)

When I initially thought about writing this piece, my brain was full of the wonderfully overwrought prose that I excel in, full of glowing descriptions of the planets I visited and the vistas I left behind. I wanted to tell the world (or more likely, the two people who actually read my blog – shout out to my wife and mum!) about what I’d seen, and beguile them with stories of my travels in deep space. But then I listened to some other people’s experiences. I listened and realised that my tales were simply not that interesting. They were interesting to me because I lived them, but when stacked up against everybody else’s they were entirely unremarkable. But then again, so were yours probably.

And you see, that’s the thing… Everyone sees something completely unique, and therefore much of the thrill is lost. The ability to capture an audience with fanciful tales of humongous spider crabs chasing me down a mountain, forcing me to dive headfirst off the cliffs and into a vivid blue lake filled with avatar-eating fish is lost when every other man/woman and his/her dog has been chased/eaten/stomped on/shot by some other weirdly wonderful creature. When Europeans set off in the 15th century to conquer, exploit and enslave the peoples and lands of the unexplored corners of the globe, they were able to capture the attention of the public precisely because they were small bands of intrepid explorers seeing and doing things that nobody else of their skin-colour persuasion had even thought possible. If everybody was setting sail for the southern continents then why would anybody care what Magellan or Drake had to say? Would Magellan and Drake even have waxed so lyrically about their buccaneering adventures if Juan Garcia next door had been stealing the gold from some other American tribe 100 miles down coast? They wouldn’t… It’s as simple as that.

So where does that leave the game and my experiences with it? Does my experience suddenly become devoid of value and wonder simply because it’s just another log-entry in the preposterously large book of weird things thrown up by NMS’s complicated mathematical algorithms? Well no of course it doesn’t. But it means that I have had to approach the game slightly differently. Eschewing the conventional NMS wisdom that the fun is to be had at the centre of the galaxy, I have, quite naturally, found myself spending inordinate amounts of time just flying around and becoming intimate with my home system(s). Beyond keeping my ship and life support systems topped up, or occasionally chancing upon an upgrade of some kind, I have interacted little with the world around me. Like an intergalactic William Wordsworth, I have strolled the lushest of plains, scaled the highest of mountains, rambled across the craggiest of landscapes, swam in the most tranquil of lakes; all simply in the name of being there and enjoying the view. 10 hours in, and I have visited five planets and a couple of space stations across two systems. That may sound like a lot, but when I hear reports of people mainlining the game in little over 30 hours, I can’t help but feel my pace is a little more relaxed than the average.

It’s a weird beast is No Man’s Sky. I have gone from the most hype, to the least hype, and seen my interest peak and trough more times than I can remember with any other game. I started in awe of the size of the thing but have since moved to an appreciation of its understated beauty. It’s a game that while occasionally frustrating is full of charm.

When I come across an alien outpost and am welcomed in with simple yet elegant Asimov-esque prose I wish there was more to it narratively. I wish there were occasional planets with hidden entrances in the ground leading to bustling subterranean cities and entire populations of aliens to converse with and learn from. I wish these things, but that is not what No Man’s Sky is about. The Euclid galaxy (the outer rims at least) is largely devoid of civilisation and that is just the way it is. There was once something there, but those societies are now dead. Perhaps this is just Sean Murray preparing us for the realities of inter-galactic travel, where even if we were suddenly able to dance our merry-way around star-systems, the chances of encountering galactic civilisations is extraordinarily low. Who knows?

Either way, No Man’s Sky is a compelling experience and one that manages to shine despite its flaws. I think the talk around it meeting, or not meeting, people’s expectations needs to be put to bed because it is tiresome to listen to. This is the game that we have and people should try to enjoy it on its own terms. What the tiny team at Hello Games have produced is a remarkable achievement and deserves better than the conversation that’s existed around it these few weeks.

Is it the last game you’ll ever need? Of course it isn’t. But it is a wondrous and often stunningly beautiful thing! Hats off to Sean Murray and Hello Games! You guys should go take a break!

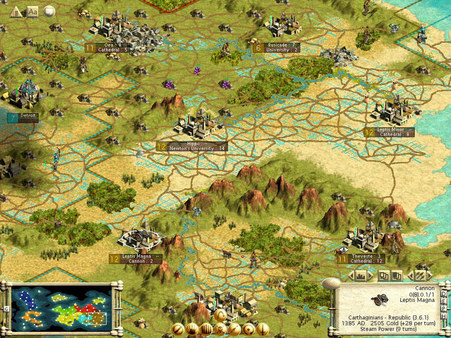

game), I was rather upset to find all the other leaders laughing and pointing at my puny nation and our feeble efforts. Here was me, Queen Elizabeth I of England, conqueror of the Spanish Armada and ruler over our nation’s golden age, smugly watching the gold pour in and the universities and libraries spring up across our lands, fully expecting the rest of the world to fawn over me in awe when really I was nothing more than a laughing stock. Suffice to say, my delusions of grandeur were quickly shot down as I found myself and my country relegated to rock bottom in pretty much every league table of note. No, I was not part of the old-hat money or culturally venerated elite, I was just another Liam Gallagher moving into a prestigious west London suburb and chucking a TV out the top floor stained glass window. The title of my saved game, “England the Glorious” would seem almost amusingly self-deprecating had it not been meant in all earnestness at the time.

game), I was rather upset to find all the other leaders laughing and pointing at my puny nation and our feeble efforts. Here was me, Queen Elizabeth I of England, conqueror of the Spanish Armada and ruler over our nation’s golden age, smugly watching the gold pour in and the universities and libraries spring up across our lands, fully expecting the rest of the world to fawn over me in awe when really I was nothing more than a laughing stock. Suffice to say, my delusions of grandeur were quickly shot down as I found myself and my country relegated to rock bottom in pretty much every league table of note. No, I was not part of the old-hat money or culturally venerated elite, I was just another Liam Gallagher moving into a prestigious west London suburb and chucking a TV out the top floor stained glass window. The title of my saved game, “England the Glorious” would seem almost amusingly self-deprecating had it not been meant in all earnestness at the time. the thing I did not realise. In Civ III, the goal is not to stockpile money, but to, as the title of the game suggests, civilise the globe.

the thing I did not realise. In Civ III, the goal is not to stockpile money, but to, as the title of the game suggests, civilise the globe.

almost reluctant to embrace the limelight that this opportunity has thrust upon him. After all, No Man’s Sky is clearly a passion piece for him, and while it would have been foolish for Hello Games to not take Sony up on their deal (whatever that deal may be), it has meant that the game is being viewed with a level of scrutiny that it would never have been had it remained just another GOG or Steam release.

almost reluctant to embrace the limelight that this opportunity has thrust upon him. After all, No Man’s Sky is clearly a passion piece for him, and while it would have been foolish for Hello Games to not take Sony up on their deal (whatever that deal may be), it has meant that the game is being viewed with a level of scrutiny that it would never have been had it remained just another GOG or Steam release.

Over the course of the past year it would not be an exaggeration to say that over 75% of my gaming time has been taken up by just two games. Made available on PS+ within a couple of months of each other, these two games have even changed my primary means of gaming. Instead of taking up valuable TV real estate with my PS4, I now find myself nightly curled up in a corner of the couch absorbed in the OLED screen of my Vita. Both games share many elements in terms of gameplay and challenge, and for those who have yet to be initiated into their club, probably appear simplistic to the point of banality. Yet, both also have huge cult followings, and also have rapidly become two of my favourite games of all time.

Over the course of the past year it would not be an exaggeration to say that over 75% of my gaming time has been taken up by just two games. Made available on PS+ within a couple of months of each other, these two games have even changed my primary means of gaming. Instead of taking up valuable TV real estate with my PS4, I now find myself nightly curled up in a corner of the couch absorbed in the OLED screen of my Vita. Both games share many elements in terms of gameplay and challenge, and for those who have yet to be initiated into their club, probably appear simplistic to the point of banality. Yet, both also have huge cult followings, and also have rapidly become two of my favourite games of all time.